The Library of Mistakes

It sounds like an Anne Tyler novel. The first time I saw the Library of Mistakes advertised in the e-newsletter Edinburgh Genealogical Society (who are nuts about all-things-researchy)...

I said, "Ah! The Library of Mistakes! This is the place for me!"

I love mistakes. I make them all the time. When I was young and stupid, I thought mistakes were to be avoided at all costs. Nowadays I recognize them as the natural, unavoidable byproduct of trying out new ideas. I make more mistakes now that I'm older, and I'm OK with that.

Mistakes remind us we are alive and growing.

Mistakes are ugly little mutts that trot along behind you, then slurp your face when you look at them. You grow to love them in spite of their ugliness.

I dunno, I think failure is more interesting than success. Perhaps it's the fiction-writer part of my brain. Success is curiously banal - there's a kind of sameness or conformity to it. Maybe it's because once someone succeeds the first time, the rest of humanity trods along the same path like sheep.

But failure, glorious failure! Is there anything more human? It is interesting in the same way all humanity is interesting - because it is messy.

Business Mistakes

An actual Library of Mistakes must have some focus though. Otherwise it would include books like Pride and Prejudice with Elizabeth mistakenly thinking Darcy was a prick. It would include every book documenting every mistake ever made. It would be ... you know, just a library.

So The Library of Mistakes primarily documents business mistakes. It was started by Dr. Stewart Hamilton, an investor based in Edinburgh. The core of the collection is essentially his old bookshelf. Dr. Hamilton was obsessed with business and economic failure, and has now shared that obsession with the public. That fact that's in Edinburgh makes perfect sense because (1) Edinburgh loves investment and (2) Edinburgh loves books.

Its express purpose is to help investors and policy makers not repeat the mistakes of the past. As George Santayana famously said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

Because - and I'm sorry if this is too obvious - business mistakes have a downside. They have human costs. The mistake of letting investors buy unlimited stocks with a 10% down payment caused the Stock Market Crash of 1929. We all know the human costs there. (And if you don't, read The Grapes of Wrath.) It might be OK to make a particular mistake once, but it'd be stupid to make it twice.

I don't understand economics or business. They're as weird to me as quantum mechanics (see https://auld-riecke.ghost.io/the-god-particle). Still, if Edinburgh has taught me anything, it's to dive headfirst into what you don't understand.

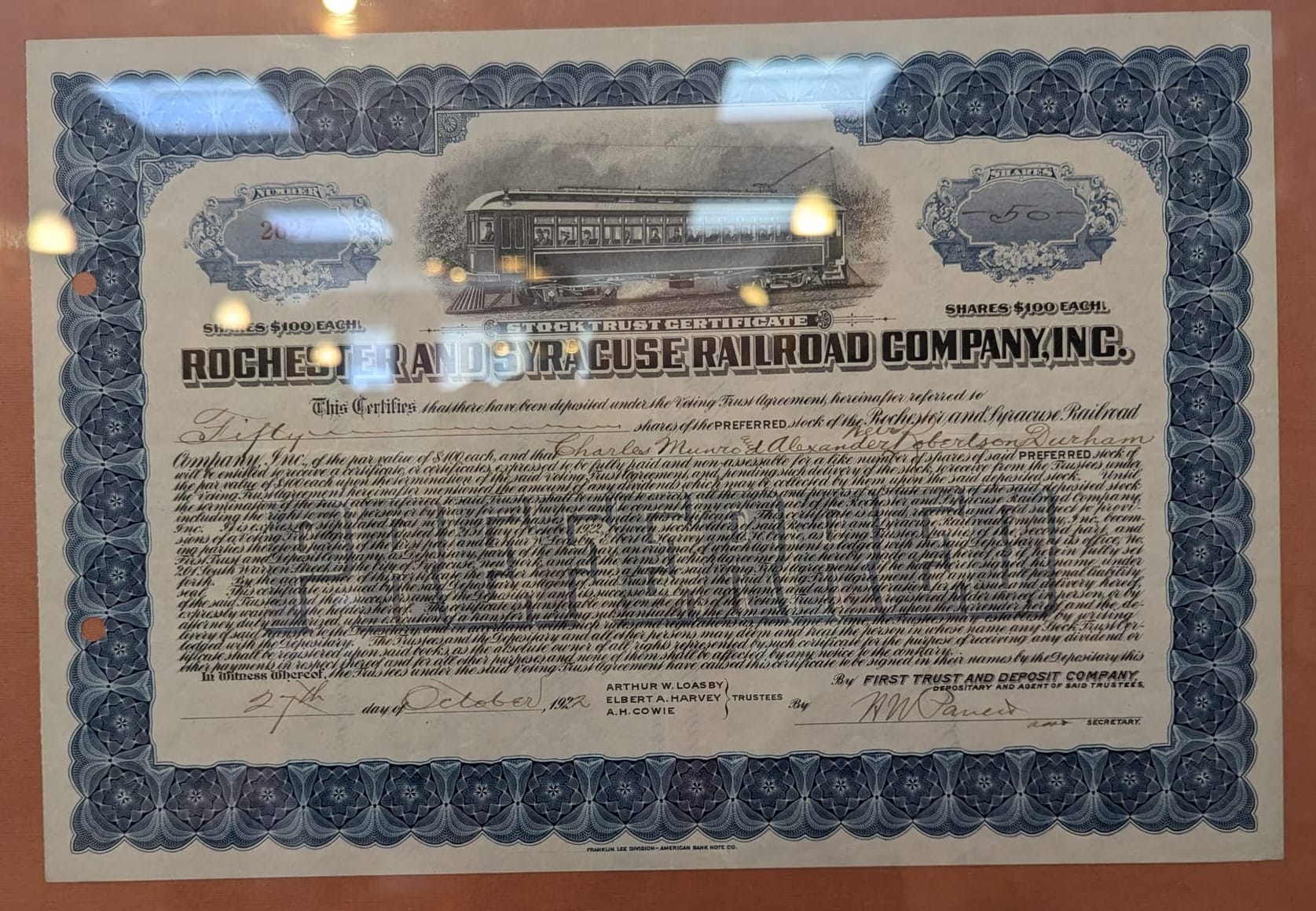

The library itself is just three blocks from our Moray Feu apartment. It is gorgeous, as all Edinburgh libraries are. The walls are chock-a-block full of the artifacts of business failures. I immediately gravitated to this gem:

Syracuse being my hometown for a little more than 20 years, I have a soft spot for it.

The mistake here was relying on the Syracuse weather. If you are from central New York, you know exactly what I mean. The company was formed by the merger of the Rochester Railroad and Syracuse Railroad, and they raised capital to build an extra line between the two cities. They were way too optimistic about finding and surveying the direct route ... and then, way too optimistic about the schedule. The clay soil of Central New York provided poor drainage, and when it rained, construction halted for days as the swampy ground tried to dry out. Once the line had been built, demand had declined to zero and the stock was sold for junk to the New York Central.

The artifacts are cool, but the crown jewel of the Library of Mistakes is the book collection. There were many books on all levels of economic failure - from individual investors, to whole companies, to entire national economies.

As I browsed through the shelves, I found a section of books dedicated to a perennially favorite subject of mine. Evidently, Dr. Hamilton was also fascinated with it. Yup. I'm talking about the largest US business failure to date, that Texas dumpster fire of a company ....

Enron.

The Grift

Enron is the biggest grift in the history of capitalism.

I love the grift, or at least studying the grift. I adore grifter movies: Paper Moon, The Sting, Ocean's Eleven, The Grifters (of course), House of Games. I'm not sure exactly why, though. The grift is interesting in its own right, I suppose, but I don't really admire grifters. I wouldn't want to be one. I wouldn't elect one to public office. (Not naming names here).

I have a theory. I like grifters because they prey on the rich, and this is all just revenge fantasy for me.

My best friend in Junior High, the late great Jeff Brandt, hated rich people. Hated them. His family was large, and his father an alcoholic, and they lived in a small house.

Jeff and I were in the same Boy Scout troop, and we knew each other pretty well. But I didn't know about his class hatred until a group of higher-tax-bracket kids joined our troop. They formed formed a den of their own, and always had pristine camping gear. They arrived in cars for the campout while Jeff rode his bike with a backpack on. They had it easy, whereas Jeff had things tough, and the disparity of it bugged him to no end. He pounced on them with vitriol, taunting them and making fun of them. To him, the rich kids den were the source of all evil.

I picked up some of that. I grew up middle class, but Jeff (and the Sex Pistols) turned me into a angry, socialist guttersnipe. That's not too far a reach for a pubescent male teenager, I guess. But it followed me far into adulthood. When I joined VISTA and worked in the bad neighborhoods in Utica, it was partly a middle finger to the rich.

Grifters prey on the get-rich-quick mentality of the privileged. They turn greed, their cardinal sin, to their own advantage. They are the short sellers of the information economy. They are the Robin Hoods with brains ... and let's face it, trick archery might be a nice parlor trick but it gets boring fast. The grift has endless variations. And in the end it takes down a wealthy person who just didn't work hard enough. The grift is a market correction.

So the rich get what's coming to them. It's karma, baby.

Except it's illegal, and there's probably a good reason for that. I guess my view is a bit more nuanced these days.

Capitalism works only if there's a free flow of truth between all participants. You make investment decisions based on the information corporations give you - "we increased our sales 50% last year". If you had to determine whether that person is lying or not, you'd be spending inordinate amounts of time just verifying facts.

That's the reason lying is illegal - lies waste time. Requiring independent verification of financial facts saves everyone a lot of legwork, and hopefully make better financial decisions. That means corporations who make more profits get more investment. That's my really simplistic view. And yeah, I know paying auditors looks like a waste of money too, but it's arguably the minimum cost of dealing with human beings. It'd be nice if everyone told the truth, but they don't, and therefore someone must be paid to root out such untruths.

Enron

And now we get to Enron. For those of you who didn't live through it, Enron was an "energy trading" company that sprung up in the early 1980's, as the energy sector was being deregulated. Supposedly they connected suppliers of energy with buyers of energy, similar to the Chicago Corn Exchange. But in fact, their business was so complicated that no one could quite figure out what they did. They mediated the energy supply chain somehow. But how? No one outside of Enron really knew.

In fact, Enron's biggest asset was misinformation. They generated a ton of it. They stockpiled it. They made money on it.

They were geniuses at misinformation. One post-mortem book on Enron is called The Smartest Guys in the Room. Reading it, you think ... that sounds about right. They had to look smarter than all the other players - the customers, the shareholders, the auditors at Arthur Andersen, and even the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Enron's standard grift, distilled to its essence, was: "You don't understand what we're doing. You can't understand it. Therefore, trust us. Here's a dividend. Now go away."

And wow, did this ever work!

Enron took control of the narrative by defining "information". And nowhere was this more apparent than mark-to-market accounting.

Let's say you own an apartment building and a renter signs a one-year lease with you, but says "I'm going to college, so I'm probably going to need this place for the next four years." The four years is a handshake agreement, but not a legal one. Your accountant is allowed to book 1 year of rent payments as an asset because your contract virtually guarantees it.

Mark-to-market accounting, however, would say the renter has made a 4 year commitment, and so you can count on 4 years of rent payments as an asset. Your rental business looks great on paper! And all you have to do is redefine a "sure thing." Never mind that the renter could simply fail to renew their 1 year lease - they are in no legal obligation, after all. In a mark-to-market setup, when the renter fails to renew, you take a loss of 3 years of rent. And business doesn't look so great. Your hope is you will sign enough future deals to hide this loss.

This was what was happening at Enron. They were counting future sales as facts, but the facts were disappearing like ants in quicksand. And here Enron, especially CFO Andrew Fastow, got really smart. He found a way to build shell corporations, move the resulting losses to these corporations, while keeping Enron's balance sheet looking good. And their accounting firm, Arthur Anderson, and the board of directors stood by.

I'm over-simplifying it here. The whole story is way more complicated, and that complication was to Enron's advantage. They were essentially money-laundering. If you make the money trail hard to follow, people will stop following the trail and rule in your favor.

Blind optimism helps. Enron looks like this new way of doing business, shiny and novel and ... if you got on the ground floor before everyone else, you could make a pile of money. You are willing to look the other way if something doesn't feel quite right.

And everyone did look the other way until whistleblowers like Sherron Watkins revealed what was actually going on. When Enron fell, it fell like a Jenga tower.

The Mistake

But let's get to the heart of this. Why was Enron a mistake? Isn't that like saying a first-degree murder is a mistake?

The mistake was believing Enron's grift. By documenting it, you hopefully prevent it from happening again, hence the Library of Mistakes.

The scapegoats in this entire fiasco, and rightly so, were the Enron Board of Directors and the accounting firm Arthur Anderson. They were supposed to be shareholder representatives, keeping an independent eye to make sure Enron business decisions were solid.

But they all had conflicts of interest. This was a fact made abundantly clear in the transcripts of a Senate inquiry ... all of which are in the Library of Mistakes. My favorite quote was from Joe Lieberman:

Gaah. There's the problem. It wasn't just the rich and the greedy who got soaked. It was the retiree who worked hard all of their lives, only to find their savings evaporated through no fault of their own.

And so the US, not wanting this to happen again, invented Sarbanes Oxley, which is over 900 pages of financial regulations. Sarbanes Oxley essentially provides more transparency into financial accounting, and makes most conflict-of-interest relationships between accounting firms illegal.

Did it work? I suppose it did. There's been no failure the size of Enron ever since ... although god knows Bernie Madoff, Elizabeth Holmes, and Sam Bankman-Fried have tried.

I discussed this with another library user, Steven, who was doing some research on the history of Canadian Banking. He pointed out that while the 900 pages of Sarbanes Oxley made US lawyers rich (because it's really difficult to understand it), Canada gets by with agreed-on principles between companies. Their economy is smaller, true. But it seems there's more than one way to prevent the grift. Sometimes it's just people standing up and saying "we don't allow grifters in here."

If Sarbanes Oxley is the legal fallout of Enron, then corporate distrust is the psychological fallout. Enron did to business what Nixon did to government. Before Watergate and Nixon, people believed the federal government was mostly working in good faith for the American people ... there might be mistakes, but there was transparency. That trust was wrecked, and hasn't really recovered.

Before Enron, few people questioned the motives of large corporations, especially those who making tidy profits. Now they always do. Or should.

Enron justifiably evoked the ire of America. There was even an Enron Joke Book. Seriously. It's in the Library of Mistakes. It's not a particularly enlightening joke book. Most of the jokes are variations on lawyer jokes, like:

Q: Why do they bury Enron senior executives at least 20 feet underground?

A: Deep down they are really good people.

But some jokes illuminate just went wrong at Enron:

Guy finds a genie bottle on the beach and rubs it. Genie pops out and says, "Thank you for releasing me. I will grant you one wish."

Guy says, "I love Hawaii, but it's such a pain to fly there. If you could build me a bridge from San Diego to Hawaii, that'd be really convenient."

Genie says, "That's physically not possible. There is not enough cement and steel in the world to build such a bridge. And the struts would need to go thousands of feet down to the bottom of the ocean. My apologies. Can you try another wish?"

Guy says, "Well, there's another thing. I lost a lot of money in Enron. I'm baffled by the whole scandal. I'd like to understand their business model. How did they accelerate revenue recognition? How did they hide their liabilities offshore? How did their individual business units work? How did they do all those wildly irregular partnership transactions right under the nose of the largest CPA firms in the world and still not get caught? Why did it take so long for the SEC and other regulators to catch up with them? I want to know everything that made Enron tick!"

Genie thinks about it. "About that bridge to Hawaii. Would you like two lanes or four?"

Put it all together - the Enron papers, the senate hearing transcripts, the tell-all books (some of which, as it turns out, had plenty of misinformation), the joke book - and you have a pretty clear outline of the mistakes.

Enron provides lessons that are still relevant. These days AI and Tech companies are all saying, "We are doing things a new way, and you cannot possibly understand it. So let us just do what we want. "

I'm just a plebe. I don't know what the proper response to this statement is. All I know is, "OK, go ahead!" is not it.

The Library

I find it oddly comforting that the Library of Mistakes exists ... and not just because it gives a good scratch for my itchy brain.

Edinburgh is filled with statues of successful old white guys. I suppose they are inspiring to some. The seagulls seem to like them anyway. And hey, better they poop on the statue's head than mine.

It's a sign of maturity that Edinburgh constructs a paeon to mistakes as well. At the very least, it shows they have a sense of humor ... one that America could learn from. But at the most, the Library of Mistakes is there to keep us humble. We do not know everything, we didn't do everything right, we've been conned. Mistakes were made.